This paper examines the likely trajectory of the Ukraine war moving forward.[1] I will address two main questions.

Written by John J. Mearsheimer

First, is a meaningful peace agreement possible? My answer is no.

We are now in a war where both sides – Ukraine and the West on one side and Russia on the other – see each other as an existential threat that must be defeated. Given maximalist objectives all around, it is almost impossible to reach a workable peace treaty. Moreover, the two sides have irreconcilable differences regarding territory and Ukraine’s relationship with the West. The best possible outcome is a frozen conflict that could easily turn back into a hot war. The worst possible outcome is a nuclear war, which is unlikely but cannot be ruled out.

Second, which side is likely to win the war?

Russia will ultimately win the war, although it will not decisively defeat Ukraine. In other words, it is not going to conquer all of Ukraine, which is necessary to achieve three of Moscow’s goals: overthrowing the regime, demilitarizing the country, and severing Kyiv’s security ties with the West. But it will end up annexing a large swath of Ukrainian territory, while turning Ukraine into a dysfunctional rump state. In other words, Russia will win an ugly victory.

Before I directly address these issues, three preliminary points are in order. For starters, I am attempting to predict the future, which is not easy to do, given that we live in an uncertain world.

Thus, I am not arguing that I have the truth; in fact, some of my claims may be proved wrong. Furthermore, I am not saying what I would like to see happen. I am not rooting for one side or the other. I am simply telling you what I think will happen as the war moves forward. Finally, I am not justifying Russian behavior or the actions of any of the states involved in the conflict. I am just explaining their actions.

Now, let me turn to substance.

Where We Are Today

To understand where the Ukraine war is headed, it is necessary to first assess the present situation. It is important to know how the three main actors – Russia, Ukraine, and the West – think about their threat environment and conceive their goals. When we talk about the West, however, we are talking mainly about the United States, since its European allies take their marching orders from Washington when it comes to Ukraine. It is also essential to understand the present situation on the battlefield. Let me start with Russia’s threat environment and its goals.

Russia’s Threat Environment

It has been clear since April 2008 that Russian leaders across the board view the West’s efforts to bring Ukraine into NATO and make it a Western bulwark on Russia’s borders as an existential threat. Indeed, President Putin and his lieutenants repeatedly made this point in the months before the Russian invasion, when it was becoming clear to them that Ukraine was almost a de facto member of NATO.[2]

Since the war began on 24 February 2022, the West has added another layer to that existential threat by adopting a new set of goals that Russian leaders cannot help but view as extremely threatening. I will say more about Western goals below but suffice it to say here that the West is determined to defeat Russia and knock it out of the ranks of the great powers, if not cause regime change or even trigger Russia to break apart like the Soviet Union did in 1991.

In a major address Putin delivered this past February (2023), he stressed that the West is a mortal threat to Russia.

“During the years that followed the breakup of the Soviet Union,” he said, “the West never stopped trying to set the post-Soviet states on fire and, most importantly, finish off Russia as the largest surviving portion of the historical reaches of our state. They encouraged international terrorists to assault us, provoked regional conflicts along the perimeter of our borders, ignored our interests and tried to contain and suppress our economy.”

He further emphasized that,

“The Western elite make no secret of their goal, which is, I quote, ‘Russia’s strategic defeat.’ What does this mean to us? This means they plan to finish us once and for all.” Putin went on to say: “this represents an existential threat to our country.”[3]

Russian leaders also see the regime in Kyiv as a threat to Russia, not just because it is closely allied with the West, but also because they see it as the offspring of the fascist Ukrainian forces that fought alongside Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union in World War II.[4]

Russia’s Goals

Russia must win this war, given that it believes that it is facing a threat to its survival. But what does victory look like? The ideal outcome before the war began in February 2022 was to turn Ukraine into a neutral state and settle the civil war in the Donbass that pitted the Ukrainian government against ethnic Russians and Russian speakers who wanted greater autonomy if not independence for their region. It appears that those goals were still realistic during the first month of the war and were in fact the basis of the negotiations in Istanbul between Kyiv and Moscow in March 2022.[5]

If the Russians had achieved those goals back then, the present war would either have been prevented or ended quickly.

But a deal that satisfies Russia’s goals is no longer in the cards.

Ukraine and NATO are joined at the hip for the foreseeable future, and neither is willing to accept Ukrainian neutrality. Furthermore, the regime in Kyiv is anathema to Russian leaders, who want it gone. They not only talk about “de-Nazifying” Ukraine, but also “demilitarizing” it, two goals that would presumably call for conquering all of Ukraine, compelling its military forces to surrender, and installing a friendly regime in Kyiv.[6]

A decisive victory of that sort is not likely to happen for a variety of reasons. The Russian army is not large enough for such a task, which would probably require at least two million men.[7]

Indeed, the existing Russian army is having difficulty conquering all the Donbass. Moreover, the West would go to enormous lengths to prevent Russia from overrunning all of Ukraine. Finally, the Russians would end up occupying huge amounts of territory that is heavily populated with ethnic Ukrainians who loathe the Russians and would fiercely resist the occupation. Trying to conquer all of Ukraine and bend it to Moscow’s will, would surely end in disaster.

Rhetoric about de-Nazifying and demilitarizing Ukraine aside, Russia’s concrete goals involve conquering and annexing a large portion of Ukrainian territory, while simultaneously turning Ukraine into a dysfunctional rump state. As such, Ukraine’s ability to wage war against Russia would be greatly reduced and it would be unlikely to qualify for membership in either the EU or NATO. Moreover, a broken Ukraine, would be especially vulnerable to Russian interference in its domestic politics. In short, Ukraine would not be a Western bastion on Russia’s border.

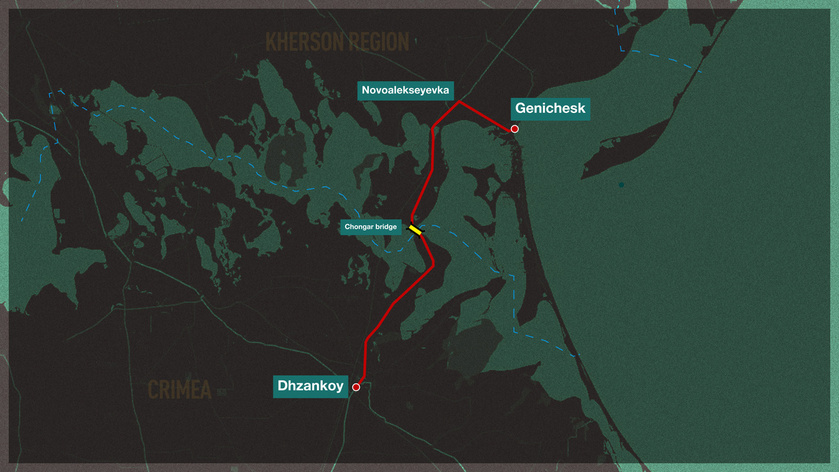

What would that dysfunctional rump state look like? Moscow has officially annexed Crimea and four other Ukrainian oblasts – Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporozhe – which together represent about 23 percent of Ukraine’s total territory before the crisis broke out in February 2014. Russian leaders have emphasized that they have no intention of surrendering that territory, some of which Russia does not yet control. In fact, there is reason to think Russia will annex additional Ukrainian territory if it has the military capability to do so at a reasonable cost. It is difficult, however, to say how much additional Ukrainian territory Moscow will seek to annex, as Putin himself makes clear.[8]

Russian thinking is likely to be influenced by three calculations.

Moscow has a powerful incentive to conquer and permanently annex Ukrainian territory that is heavily populated with ethnic Russians and Russian speakers.

It will want to protect them from the Ukrainian government – which has become hostile to all things Russian – and make sure there is no civil war anywhere in Ukraine like the one that took place in the Donbass between February 2014 and February 2022.

At the same time, Russia will want to avoid controlling territory largely populated by hostile ethnic Ukrainians, which places significant limits on further Russian expansion. Finally, turning Ukraine into a dysfunctional rump state will require Moscow to take substantial amounts of Ukrainian territory so it is well-positioned to do significant damage to its economy. Controlling all of Ukraine’s coastline along the Black Sea, for example, would give Moscow significant economic leverage over Kyiv.

Those three calculations suggest that Russia is likely to attempt to annex the four oblasts – Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, Mykolaiv, and Odessa – that are immediately to the west of the four oblasts it has already annexed – Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporozhe. If that were to happen, Russia would control approximately 43 percent of Ukraine’s pre-2014 territory.[9]

Dmitri Trenin, a leading Russian strategist estimates that Russian leaders would seek to take even more Ukrainian territory – pushing westward in northern Ukraine to the Dnieper River and taking the part of Kyiv that sits on the east bank of that river. He writes that “A logical next step” after taking all of Ukraine from Kharkiv to Odessa “would be to expand Russian control to all of Ukraine east of the Dnieper River, including the part of Kyiv that lies on the that river’s eastern bank. If that were to happen, the Ukrainian state would shrink to include only the central and western regions of the country.”[10]

The West’s Threat Environment

It might seem hard to believe now, but before the Ukraine crisis broke out in February 2014, Western leaders did not view Russia as a security threat. NATO leaders, for example, were talking with Russia’s president about “a new stage of cooperation towards a true strategic partnership” at the alliance’s 2010 Summit in Lisbon.[11]

Unsurprisingly, NATO expansion before 2014 was not justified in terms of containing a dangerous Russia. In fact, it was Russian weakness that allowed the West to shove the first two tranches of NATO expansion in 1999 and 2004 down Moscow’s throat and then allowed the George W. Bush administration to think in 2008 that Russia could be forced to accept Georgia and Ukraine joining the alliance. But that assumption proved wrong and when the Ukraine crisis broke out in 2014, the West suddenly began portraying Russia as a dangerous foe that had to be contained if not weakened.[12]

Since the war started in February 2022, the West’s perception of Russia has steadily escalated to the point where Moscow now appears to be seen as an existential threat. The United States and its NATO allies are deeply involved in Ukraine’s war against Russia. Indeed, they are doing everything but pulling the triggers and pushing the buttons.[13]

Moreover, they have made clear their unequivocal commitment to winning the war and maintaining Ukraine’s sovereignty. Thus, losing the war would have hugely negative consequences for Washington and for NATO. America’s reputation for competence and reliability would be badly damaged, which would affect how its allies as well as its adversaries – especially China – deal with the United States. Furthermore, virtually every European country in NATO believes that the alliance is an irreplaceable security umbrella. Thus, the possibility that NATO might be badly damaged – maybe even wrecked – if Russia wins in Ukraine is cause for profound concern among its members.

In addition, Western leaders frequently portray the Ukraine war as an integral part of a larger global struggle between autocracy and democracy that is Manichean at its core. On top of that, the future of the sacrosanct rules-based international order is said to depend on prevailing against Russia. As King Charles said this past March (2023), “The security of Europe as well as our democratic values are under threat.”[14]

Similarly, a resolution introduced in the U.S. Congress in April declares: “United States interests, European security, and the cause of international peace depend on … Ukrainian victory.”[15]

A recent article in The Washington Post, captures how the West treats Russia as an existential threat: “Leaders of the more than 50 other countries backing Ukraine have couched their support as part of an apocalyptic battle for the future of democracy and the international rule of law against autocracy and aggression that the West cannot afford to lose.”[16]

The West’s Goals

As should be clear, the West is staunchly committed to defeating Russia. President Biden has repeatedly said that the United States is in this war to win. “Ukraine will never be a victory for Russia.” It must end in “strategic failure.” Washington, he emphasizes, will stay in the fight “for as long as it takes.”[17]

Specifically, the aim is to defeat Russia’s army in Ukraine – erasing its territorial gains – and cripple its economy with lethal sanctions. If successful, Russia would be knocked out of the ranks of the great powers, weakening it to the point where it could not threaten to invade Ukraine again.[18]

Western leaders have additional goals, which include regime change in Moscow, putting Putin on trial as a war criminal, and possibly breaking up Russia into smaller states.[19]

At the same time, the West remains committed to bringing Ukraine into NATO, although there is disagreement within the alliance about when and how that will happen.[20]

Jens Stoltenberg, the alliance’s secretary general told a news conference in Kyiv in April (2023) that “NATO’s position remains unchanged and that Ukraine will become a member of the alliance.” At the same time, he emphasized that “The first step toward any membership of Ukraine to NATO is to ensure that Ukraine prevails, and that is why the U.S. and its partners have provided unprecedented support for Ukraine.”[21]

Given these goals, it is clear why Russia views the West as an existential threat.

Ukraine’s Threat Environment and Goals

There is no doubt that Ukraine faces an existential threat, given that Russia is bent on dismembering it and making sure that the surviving rump state is not only economically weak, but is neither a de facto nor a de jure member of NATO. There is also no question that Kyiv shares the West’s goal of defeating and seriously weakening Russia, so that it can regain its lost territory and keep it under Ukrainian control forever. As President Zelensky recently told President Xi Jinping, “There can be no peace that is based on territorial compromises.”[22]

Ukrainian leaders naturally remain steadfastly committed to joining the EU and NATO and making Ukraine an integral part of the West.[23]

In sum, the three key actors in the Ukraine war all believe they face an existential threat, which means each of them thinks it must win the war or else suffer terrible consequences.

The Battlefield Today

Turning to events on the battlefield, the war has evolved into war of attrition where each side is principally concerned with bleeding the other side white, causing it to surrender. Of course, both sides are also concerned with capturing territory, but that goal is of secondary importance to wearing down the other side.

The Ukrainian military had the upper hand in the latter half of 2022, which allowed it to take back territory from Russia in the Kharkiv and Kherson regions. But Russia responded to those defeats by mobilizing 300,000 additional troops, reorganizing it army, shortening its front lines, and learning from its mistakes.[24]

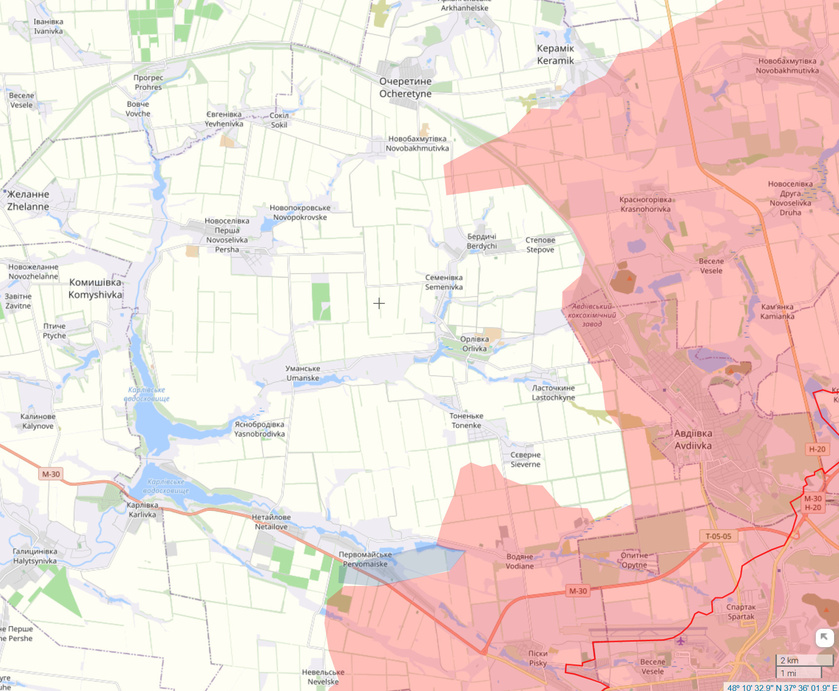

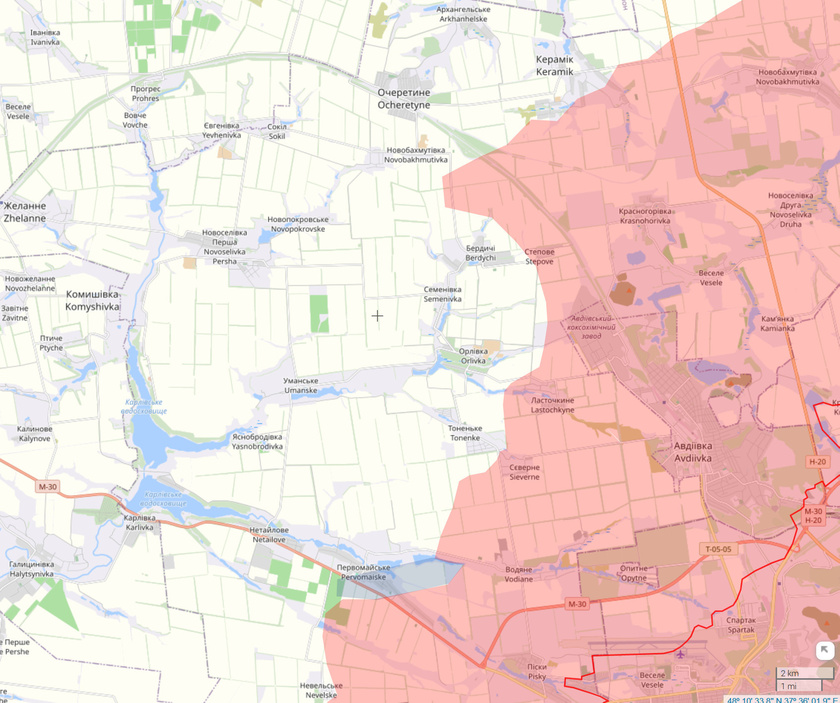

The locus of the fighting in 2023 has been in eastern Ukraine, mainly in the Donetsk and Zaporozhe regions. The Russians have had the upper hand this year, mainly because they have a substantial advantage in artillery, which is the most important weapon in attrition warfare.

Moscow’s advantage was evident in the battle for Bakhmut, which ended when the Russians captured that city in late May (2023). Although it took Russian forces ten months to take control of Bakhmut they inflicted huge casualties on Ukrainian forces with their artillery.[25]

Shortly thereafter on 4 June, Ukraine launched its long-awaited counter-offensive at different locations in the Donetsk and Zaporozhe regions. The aim is to penetrate Russia’s front lines of defense, deliver a staggering blow to Russian forces, and take back a substantial amount of Ukrainian territory that is now under Russian control. In essence, the aim is to duplicate Ukraine’s successes in Kharkiv and Kherson in 2022.

Ukraine’s army has made little progress so far in achieving those goals and instead is bogged down in deadly attrition battles with Russian forces. In 2022, Ukraine was successful in the Kharkiv and Kherson campaigns because its army was fighting against outnumbered and overextended Russian forces. That is not the case today: Ukraine is attacking into the face of well-prepared lines of Russian defense. But even if Ukrainian forces break through those defensive lines, Russian troops will quickly stabilize the front and the attrition battles will continue.[26]

The Ukrainians are at a disadvantage in these encounters because the Russians have a significant firepower advantage.

Where We Are Headed

Let me switch gears and move away from the present and talk about the future, starting with how events on the battlefield are likely to play out moving forward. As noted, I believe Russia will win the war, which means it will end up conquering and annexing substantial Ukrainian territory, leaving Ukraine as a dysfunctional rump state. If I am correct, this will be a grievous defeat for Ukraine and the West.

There is a silver lining in this outcome, however: a Russian victory markedly reduces the threat of nuclear war, as nuclear escalation is most likely to occur if Ukrainian forces are winning victories on the battlefield and threatening to take back all or most of the territories Kyiv has lost to Moscow. Russian leaders would surely think seriously about using nuclear weapons to rescue the situation. Of course, if I am wrong about where the war is headed and the Ukrainian military gains the upper hand and begins pushing Russian forces eastward, the likelihood of nuclear use would increase significantly, which is not to say it would be a certainty.

What is the basis of my claim that the Russians are likely to win the war?

The Ukraine war, as emphasized, is a war of attrition in which capturing and holding territory is of secondary importance. The aim in attrition warfare is to wear down the other side’s forces to the point where it either quits the fight or is so weakened that it can no longer defend contested territory.[27]

Who wins an attrition war is largely a function of three factors: the balance of resolve between the two sides; the population balance between them; and the casualty-exchange ratio. The Russians have a decisive advantage in population size and a marked advantage in the casualty-exchange ratio; the two sides are evenly matched in terms of resolve.

Consider the balance of resolve. As noted, both Russia and Ukraine believe they are facing an existential threat, and naturally, both sides are fully committed to winning the war. Thus, it is hard to see any meaningful difference in their resolve. Regarding population size, Russia had approximately a 3.5:1 advantage before the war began in February 2022. Since then, the ratio has shifted noticeably in Russia’s favor. About eight million Ukrainians have fled the country, subtracting from Ukraine’s population. Roughly three million of those emigrants have gone to Russia, adding to its population. In addition, there are probably about four million other Ukrainian citizens living in the territories that Russia now controls, further shifting the population imbalance in Russia’s favor. Putting those numbers together gives Russia approximately a 5:1 advantage in population size.[28]

Finally, there is the casualty-exchange ratio, which has been a controversial issue since the war started in February 2022. The conventional wisdom in Ukraine and the West is that the casualty levels on both sides are either roughly equal or that the Russians have suffered greater casualties than the Ukrainians. The head of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, Oleksiy Danilov, goes so far as to argue that the Russian lost 7.5 soldiers for every one Ukrainian soldier in the battle for Bakhmut.[29]

A Ukrainian soldier adds wood to a fire to stave off the bitter cold, Bakhmut, Donbass (File photo)

These claims are wrong. Ukrainian forces have surely suffered much greater casualties than their Russian opponents for one reason: Russia has much more artillery than Ukraine.

In attrition warfare, artillery is the most important weapon on the battlefield. In the U.S. Army, artillery is widely known as the “king of battle,” because it is principally responsible for killing and wounding the soldiers doing the fighting.[30]

Thus, the balance of artillery matters enormously in a war of attrition. By almost every account, the Russians have somewhere between a 5:1 and a 10:1 advantage in artillery, which puts the Ukrainian army at a significant disadvantage on the battlefield.[31]

Ceteris paribus, one would expect the casualty-exchange ratio to approximate the balance of artillery. Ergo, a casualty-exchange ratio on the order of 2:1 in Russia’s favor is a conservative estimate.[32]

One possible challenge to my analysis is to argue that Russia is the aggressor in this war, and the offender invariably suffers much higher casualty levels than the defender, especially if the attacking forces are engaged in broad frontal assaults, which is often said to be the Russian military’s modus operandi.[33]

After all, the offender is out in the open and on the move, while the defender is mainly fighting from fixed positions that provide substantial cover. This logic underpins the famous 3:1 rule of thumb, which says that an attacking force needs at least three times as many soldiers as the defender to win a battle.[34]

But there are problems with this line of argument when it is applied to the Ukraine war.

First, it is not just the Russians who have initiated offensive campaigns over the course of the war.[35]

Indeed, the Ukrainians launched two major offensives last year that led to widely heralded victories: the Kharkiv offensive in September 2022 and the Kherson offensive between August and November 2022. Although the Ukrainians made substantial territorial gains in both campaigns, Russian artillery inflicted heavy casualties on the attacking forces. The Ukrainians just began another major offensive on 4 June against Russian forces that are more numerous and far better prepared than those the Ukrainians fought against in Kharkiv and Kherson.

Second, the distinction between offenders and defenders in a major battle is usually not black and white. When one army attacks another army, the defender invariably launches counterattacks. In other words, the defender transitions to the offense and the offender transitions to the defense. Over the course of a protracted battle, each side is likely to end up doing much attacking and counterattacking as well as defending fixed positions. This back and forth explains why the casualty-exchange ratios in US Civil War battles and WWI battles are often roughly equal, not favorable to the army that started out on the defensive. In fact, the army that strikes the first blow occasionally suffers less casualties than the target army.[36]

In short, defense usually involves a lot of offense.

It is clear from Ukrainian and Western news accounts that Ukrainian forces frequently launch counterattacks against Russian forces. Consider this account in The Washington Post of the fighting earlier this year in Bakhmut: “‘There is this fluid motion going on.’ said a Ukrainian first lieutenant … Russian attacks along the front allow their forces to advance a few hundred meters before being pushed back hours later. ‘It’s hard to distinguish exactly where the front line is because it moves like Jell-O,’ he said.”[37]

Given Russia’s massive artillery advantage, it seems reasonable to assume that the casualty-exchange ratio in these Ukrainian counterattacks favors the Russians – probably in a lopsided way.

Third, the Russians are not employing – at least not often – large-scale frontal assaults that aim to rapidly move forward and capture territory, but which would expose the attacking forces to withering fire from Ukrainian defenders. As General Sergey Surovikin explained in October 2022, when he was commanding the Russian forces in Ukraine, “We have a different strategy… We spare each soldier and are persistently grinding down the advancing enemy.”[38]

In effect, Russian troops have adopted clever tactics that reduce their casualty levels.[39]

Their favored tactic is to launch probing attacks against fixed Ukrainian positions with small infantry units, which causes Ukrainian forces to attack them with mortars and artillery.[40]

That response allows the Russians to determine where the Ukrainian defenders and their artillery are located. The Russians then use their great advantage in artillery to pound their adversaries. Afterwards, packets of Russian infantry move forward again; and when they meet serious Ukrainian resistance, they repeat the process. These tactics help explain why Russia is making slow progress in capturing Ukrainian held territory.

One might think the West can go a long way toward evening out the casualty-exchange ratio by supplying Ukraine with many more artillery tubes and shells, thus eliminating Russia’s significant advantage with this critically important weapon. That is not going to happen anytime soon, however, simply because neither the United States nor its allies have the industrial capacity necessary to mass produce artillery tubes and shells for Ukraine. Nor can they rapidly build that capacity.[41]

The best the West can do – at least for the next year or so – is maintain the existing imbalance of artillery between Russia and Ukraine, but even that will be a difficult task.

Ukraine can do little to help remedy the problem, because its ability to manufacture weapons is limited. It is almost completely dependent on the West, not only for artillery, but for every type of major weapons system. Russia, on the other hand, had a formidable capability to manufacture weaponry going into the war, which has been ramped up since the fighting started. Putin recently said: “Our defense industry is gaining momentum every day. We have increased military production by 2.7 times during the last year. Our production of the most critical weapons has gone up ten times and keeps increasing. Plants are working in two or three shifts, and some are busy around the clock.”[42]

In short, given the sad state of Ukraine’s industrial base, it is in no position to wage a war of attrition by itself. It can only do so with Western backing. But even then, it is doomed to lose.

There has been a recent development that further increases Russia’s firepower advantage over Ukraine. For the first year of the war, Russian airpower had little influence on what happened in the ground war, mainly because Ukraine’s air defenses were effective enough to keep Russian aircraft far away from most battlefields. But the Russians have seriously weakened Ukraine’s air defenses, which now allows the Russian air force to strike Ukrainian ground forces on or directly behind the front lines.[43]

In addition, Russia has developed the capability to equip its huge arsenal of 500 kg iron bombs with guidance kits that make them especially lethal.[44]

In sum, the casualty-exchange ratio will continue to favor the Russians for the foreseeable future, which matters enormously in a war of attrition. In addition, Russia is much better positioned to wage attrition warfare because its population is far larger than Ukraine’s. Kyiv’s only hope for winning the war is for Moscow’s resolve to collapse, but that is unlikely given that Russian leaders view the West as an existential danger.

Prospects for A Negotiated Peace Agreement

There is a growing chorus of voices around the world calling for all sides in the Ukrainian war to embrace diplomacy and negotiate a lasting peace agreement. This is not going to happen, however. There are too many formidable obstacles to ending the war anytime soon, much less fashioning a deal that produces a durable peace. The best possible outcome is a frozen conflict, where both sides continue looking for opportunities to weaken the other side and where there is an ever-present danger of renewed fighting.

At the most general level, peace is not possible because each side views the other as a mortal threat that must be defeated on the battlefield. There is hardly any room for compromise with the other side in these circumstances. There are also two specific points of dispute between the warring parties that are unsolvable. One involves territory while the other concerns Ukrainian neutrality.[45]

Almost all Ukrainians are deeply committed to getting back all their lost territory – including Crimea.[46]

Who can blame them? But Russia has officially annexed Crimea, Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporozhe, and is firmly committed to keeping that territory. In fact, there is reason to think Moscow will annex more Ukrainian territory if it can.

The other Gordian knot concerns Ukraine’s relationship with the West. For understandable reasons, Ukraine wants a security guarantee once the war ends, which only the West can provide. That means either de facto or de jure membership in NATO, since no other countries can protect Ukraine. Virtually all Russian leaders, however, demand a neutral Ukraine, which means no military ties with the West and thus no security umbrella for Kyiv. There is no way to square this circle.

There are two other obstacles to peace: nationalism, which has now morphed into hypernationalism, and the complete lack of trust on the Russian side.

Nationalism has been a powerful force in Ukraine for well over a century, and antagonism toward Russia has long been one of its core elements. The outbreak of the present conflict on 22 February 2014 fueled that hostility, prompting the Ukrainian parliament to pass a bill the following day that restricted the use of Russian and other minority languages, a move that helped precipitate the civil war in the Donbass.[47]

Russia’s annexation of Crimea shortly thereafter made a bad situation worse. Contrary to the conventional wisdom in the West, Putin understood that Ukraine was a separate nation from Russia and that the conflict between the ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers living in the Donbass and the Ukrainian government was all about “the national question.”[48]

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, which directly pits the two countries against each other in a protracted and bloody war has turned that nationalism into hypernationalism on both sides. Contempt and hatred of “the other” suffuses Russian and Ukrainian society, which creates powerful incentives to eliminate that threat – with violence if necessary. Examples abound. A prominent Kyiv weekly maintains that famous Russian authors like Mikhail Lermontov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Boris Pasternak are “killers, looters, ignoramuses.”[49]

Russian culture, says a prominent Ukrainian writer, represents “barbarism, murder, and destruction …. Such is the fate of the culture of the enemy.”[50]

Predictably, the Ukrainian government is engaged in “de-Russification” or “decolonization,” which involves purging libraries of books by Russian authors, renaming streets that have names with links to Russia, pulling down statues of figures like Catherine the Great, banning Russian music produced after 1991, breaking ties between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church, and minimizing use of the Russian language. Perhaps Ukraine’s attitude toward Russia is best summed up by Zelensky’s terse comment: “We will not forgive. We will not forget.”[51]

Turning to the Russian side of the hill, Anatol Lieven reports that “every day on Russian TV you can see hate-filled ethnic insults directed at Ukrainians.”[52]

Unsurprisingly, the Russians are working to Russify and erase Ukrainian culture in the areas that Moscow has annexed. These measures include issuing Russian passports, changing the curricula in schools, replacing the Ukrainian hryvnia with the Russian ruble, targeting libraries and museums, and renaming towns and cities.[53]

Bakhmut, for example, is now Artemovsk and the Ukrainian language is no longer taught in schools in the Donetsk region.[54]

Apparently, the Russians too will neither forgive nor forget.

The rise of hypernationalism is predictable in wartime, not only because governments rely heavily on nationalism to motivate their people to back their country to the hilt, but also because the death and destruction that come with war – especially protracted wars – pushes each side to dehumanize and hate the other. In the Ukraine case, the bitter conflict over national identity adds fuel to the fire.

Hypernationalism naturally makes it harder for each side to cooperate with the other and gives Russia reason to seize territory that is filled with ethnic Russians and Russian speakers. Presumably, many of them would prefer living under Russian control, given the animosity of the Ukrainian government toward all things Russian. In the process of annexing these lands, the Russians are likely to expel large numbers of ethnic Ukrainians, mainly because of fear that they will rebel against Russian rule if they remain. These developments will further fuel hatred between Russians and Ukrainians, making compromise over territory practically impossible.

There is a final reason why a lasting peace agreement is not doable. Russian leaders do not trust either Ukraine or the West to negotiate in good faith, which is not to imply that Ukrainian and Western leaders trust their Russian counterparts. Lack of trust is evident on all sides, but it is especially acute on Moscow’s part because of a recent set of revelations.

The source of the problem is what happened in the negotiations over the 2015 Minsk II Agreement, which was a framework for shutting down the conflict in the Donbass. French President Francois Hollande and German Chancellor Angela Merkel played the central role is designing that framework, although they consulted extensively with both Putin and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. Those four individuals were also the key players in the subsequent negotiations. There is little doubt that Putin was committed to making Minsk work. But Hollande, Merkel, and Poroshenko – as well as Zelensky – have all made it clear that they were not interested in implementing Minsk, but instead saw it as an opportunity to buy time for Ukraine to build up its military so that it could deal with the insurrection in the Donbass. As Merkel told Die Zeit, it was “an attempt to give Ukraine time … to become stronger.”[55]

Similarly, Poroshenko said, “Our goal was to, first, stop the threat, or at least to delay the war — to secure eight years to restore economic growth and create powerful armed forces.”[56]

Shortly after Merkel’s Die Zeit interview in December 2022, Putin told a press conference: “I thought the other participants of this agreement were at least honest, but no, it turns out they were also lying to us and only wanted to pump Ukraine with weapons and get it prepared for a military conflict.” He went on to say that getting bamboozled by the West had caused him to pass up an opportunity to solve the Ukraine problem in more favorable circumstances for Russia: “Apparently, we got our bearings too late, to be honest. Maybe we should have started all this [the military operation] earlier, but we just hoped that we would be able to solve it within the framework of the Minsk agreements.” He then made it clear that the West’s duplicity would complicate future negotiations: “Trust is already almost at zero, but after such statements, how can we possibly negotiate? About what? Can we make any agreements with anybody and where are the guarantees?”[57]

In sum, there is hardly any chance the Ukraine war will end with a meaningful peace settlement. The war is instead likely to drag on for at least another year and eventually turn into a frozen conflict that might turn back into a shooting war.

Consequences

The absence of a viable peace agreement will have a variety of terrible consequences. Relations between Russia and the West, for example, are likely to remain profoundly hostile and dangerous for the foreseeable future. Each side will continue demonizing the other while working hard to maximize the amount of pain and trouble it causes its rival. This situation will certainly prevail if the fighting continues; but even if the war turns into a frozen conflict, the level of hostility between the two sides is unlikely to change much.

Moscow will seek to exploit existing fissures between European countries, while also working to weaken the trans-Atlantic relationship as well as key European institutions like the EU and NATO. Given the damage the war has done to Europe’s economy and continues to do, given the growing disenchantment in Europe with the prospect of a never-ending war in Ukraine, and given the differences between Europe and the United States regarding trade with China, Russian leaders should find fertile ground for causing trouble in the West.[58]

This meddling will naturally reinforce Russophobia in Europe and the United States, making a bad situation worse.

The West, for its part, will maintain sanctions on Moscow and keep economic intercourse between the two sides to a minimum, all for the purpose of harming Russia’s economy. Moreover, it will surely work with Ukraine to help generate insurgencies in the territories Russia took from Ukraine. At the same time, the United States and its allies will continue pursuing a hard-nosed containment policy toward Russia, which many believe will be enhanced by Finland and Sweden joining NATO and the deployment of significant NATO forces in eastern Europe.[59]

Of course, the West will remain committed to bringing Georgia and Ukraine into NATO, even if that is unlikely to happen. Finally, U.S. and European elites are sure to retain their enthusiasm for fostering regime change in Moscow and putting Putin on trial for Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

Not only will relations between Russia and the West remain poisonous moving forward, but they will also be dangerous, as there will be the ever-present possibility of nuclear escalation or a great-power war between Russia and the United States.[60]

The Destruction of Ukraine

Ukraine was in severe economic and demographic trouble before the war began last year.[61]

The devastation inflicted on Ukraine since the Russian invasion is horrific. Surveying events during the war’s first year, the World Bank declares that the invasion “has dealt an unimaginable toll on the people of Ukraine and the country’s economy, with activity contracting by a staggering 29.2 percent in 2022.” Unsurprisingly, Kyiv needs massive injections of foreign aid just to keep the government running, not to mention fighting the war. Furthermore, the World Bank estimates that damages exceed $135 billion and that roughly $411 billion will be needed to rebuild Ukraine. Poverty, it reports, “increased from 5.5 percent in 2021 to 24.1 percent in 2022, pushing 7.1 million more people into poverty and retracting 15 years of progress.”[62]

Cities have been destroyed, roughly 8 million Ukrainians have fled the country, and about 7 million are internally displaced. The United Nations has confirmed 8,490 civilian deaths, although it believes that the actual number is “considerably higher.”[63]

And surely Ukraine has suffered well over 100,000 battlefield casualties.

Ukraine’s future looks bleak in the extreme. The war shows no signs of ending anytime soon, which means more destruction of infrastructure and housing, more destruction of towns and cities, more civilian and military deaths, and more damage to the economy. And not only is Ukraine likely to lose even more territory to Russia, but according to the European Commission, “the war has set Ukraine on a path of irreversible demographic decline.”[64]

To make matters worse, the Russians will work overtime to keep rump Ukraine economically weak and politically unstable. The ongoing conflict is also likely to fuel corruption, which has long been an acute problem, and further strengthen extremist groups in Ukraine. It is hard to imagine Kyiv ever meeting the criteria necessary for joining either the EU or NATO.

US Policy Toward China

The Ukraine war is hindering the U.S. effort to contain China, which is of paramount importance for American security since China is a peer competitor while Russia is not.[65]

Indeed, balance-of-power logic says that the United States should be allied with Russia against China and pivoting full force to East Asia. Instead, the war in Ukraine has pushed Beijing and Moscow close together, while providing China with a powerful incentive to make sure that Russia is not defeated and the United States remains tied down in Europe, impeding its efforts to pivot to East Asia.

Conclusion

It should be apparent by now that the Ukraine war is an enormous disaster that is unlikely to end anytime soon and when it does, the result will not be a lasting peace. A few words are in order about how the West ended up in this dreadful situation.

The conventional wisdom about the war’s origins is that Putin launched an unprovoked attack on 24 February 2022, which was motivated by his grand plan to create a greater Russia. Ukraine, it is said, was the first country he intended to conquer and annex, but not the last. As I have said on numerous occasions, there is no evidence to support this line of argument, and indeed there is considerable evidence that directly contradicts it.[66]

While there is no question Russia invaded Ukraine, the ultimate cause of the war was the West’s decision – and here we are talking mainly about the United States – to make Ukraine a Western bulwark on Russia’s border. The key element in that strategy was bringing Ukraine into NATO, a move that not only Putin, but the entire Russian foreign policy establishment, saw as an existential threat that had to be eliminated.

It is often forgotten that numerous American and European policymakers and strategists opposed NATO expansion from the start because they understood that the Russians would see it as a threat, and that the policy would eventually lead to disaster. The list of opponents includes George Kennan, both President Clinton’s Secretary of Defense, William Perry, and his Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General John Shalikashvili, Paul Nitze, Robert Gates, Robert McNamara, Richard Pipes, and Jack Matlock, just to name a few.[67]

At the NATO summit in Bucharest In April 2008, both French President Nicolas Sarkozy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel opposed President George W. Bush’s plan to bring Ukraine into the alliance. Merkel later said that her opposition was based on her belief that Putin would interpret it as a “declaration of war.”[68]

Of course, the opponents of NATO expansion were correct, but they lost the fight and NATO marched eastward, which eventually provoked the Russians to launch a preventive war. Had the United States and its allies not moved to bring Ukraine into NATO in April 2008, or had they been willing to accommodate Moscow’s security concerns after the Ukraine crisis broke out in February 2014, there probably would be no war in Ukraine today and its borders would look like they did when it gained its independence in 1991. The West made a colossal blunder, which it and many others are not done paying for.

Notes

- 1 This paper was written to serve as the basis for public talks I have given or will give on the Ukraine conflict. See, for example: this.

- 2 https://nationalinterest.org/feature/causes-and-consequences-ukraine-crisis-203182https://jmss.org/article/view/76584https://harpers.org/archive/2023/06/why-are-we-in-ukraine/https://nationalinterest.org/feature/course-correcting-toward-diplomacy-ukraine-crisis-204171https://www.amazon.com/How-West-Brought-Ukraine-Understanding/dp/0991076702/ref=pd_vtp_h_vft_none_pd_vtp_h_vft_none_sccl_1/142-3537937-6121237?pd_rd_w=ezoTp&content-id=amzn1.sym.a5610dee-0db9-4ad9-a7a9-14285a430f83&pf_rd_p=a5610dee-0db9-4ad9-a7a9-14285a430f83&pf_rd_r=ZGPKTJ5C49MCEE3RVTNG&pd_rd_wg=TaIQh&pd_rd_r=a9e88789-cd82-47ab-95d8-03165a6f271b&pd_rd_i=0991076702&psc=1https://scheerpost.com/2022/04/09/former-nato-military-analyst-blows-the-whistle-on-wests-ukraine-invasion-narrative/

3 http://www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/70565 - 4 http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/71445

- http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/71391

5 https://nationalinterest.org/feature/course-correcting-toward-diplomacy-ukraine-crisis-204171; https://tass.com/politics/1634479 - 6 http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/7139