Western Media Has Falsely Presented the Donbass Drive For Autonomy as Being Instigated By Moscow

In Reality It Resulted Largely from Kyiv’s Destruction of Eastern Ukraine’s Economy Under Neo-Liberal Economic Policies Pushed by Washington Since the 1990s

The war in Ukraine is commonly seen through one of two lenses. The vision presented by Western, NATO-aligned powers is one of an astro-turfed Donbas separatism created by Moscow to justify the division of Ukraine.

The view of NATO’s critics is that the Donbas republics rebelled against the Euromaidan revolution and the country’s nationalistic, Euro-centric tilt. The reality is that this conflict started much earlier and was merely frozen until the overthrow of the Ukrainian government in 2013.

Political Economy of the Donbas

Global Security outlines the economic situation in Donbas at the time of the dissolution of the USSR.

The Donetsk basin had been settled by Russian and Bessarabian people in the 18th century, after the steppes of Ukraine and the coasts of the Black and Azov Seas were added to the Russian Empire.

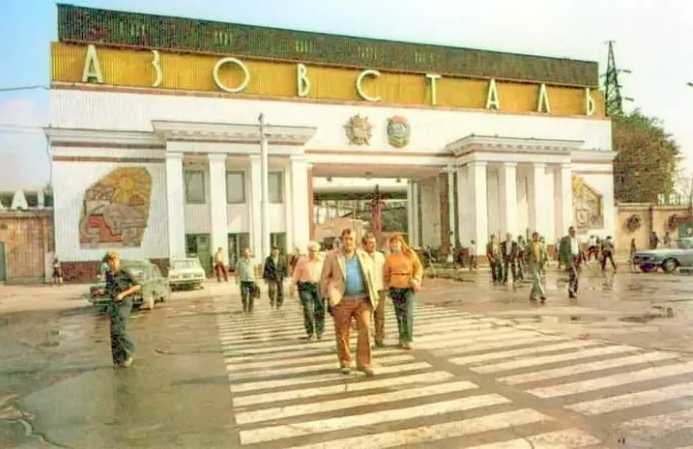

Donbas h

eld enormous reserves of coal, which were vital to the industrialization of the Empire and, later, the Soviet Union. During Soviet times Donbas became the industrial center of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, with major iron mines in Krivoy Rog, the massive “Azovstal” steelworks, and the manufacture of machine parts for the defense and space industries.

Coal miners were able to exert political power throughout the industrial age by staging widespread strikes. Major strikes in August and September 1962 were held in Donbas and neighboring regions, resulting in promises of extra pay and threats of military force from the authorities.

Another wave of Donbas strikes in 1989 received concessions from the central government and the strike committees were effectively left in control of mining towns instead of the Communist Party.

The tension between the central government and the Donbas miners was fueled by the increasing difficulty (and cost) of pulling coal from Donbas mines. Other coal-mining regions of the USSR were less costly but the social unrest in Donbas was placated with increasing state subsidies.

Ukrainian independence ended the Donbas struggle against Moscow but created intractable economic problems. The extensive subsidies for Donbas mines were shifted to the less wealthy government in Kyiv, the economic integration of the Soviet Union’s republics was disrupted, and the shift to a market economy was disastrous.

After the break-up of the Union, the political leaders of the Donbas miners would become known as “red directors,” socialists who put the interconnected economic needs of the Donbas and surrounding regions at the heart of their demands to Kyiv.

One of the earliest separatist organizations in Ukraine was the International Movement of Donbas. The Ukrainian news site DEPO, citing Novosti Donbas, describes the origin of the Intermovement as a project of academics at Donetsk University. The group was created as the “International Front for Donbas” at a meeting held on August 31, 1989.

The “Interfront” was clearly inspired by the Intermovement of Estonia, which had formed the year before to defend communism and the Union state from Estonian separatists. In the summer of 1990 two of the leading figures of the Interfront, the brothers Dmitry and Vladimir Kornilov, traveled to the Baltics and western Ukraine. On this trip they studied the Intermovement of Estonia and its parallel organizations in Lithuania and Latvia, as well as the anti-Soviet People’s Movement of Ukraine (“Rukh”) based in Lviv.

The founding conference of the Intermovement of Donbas was held on November 18, 1990, and the Kornilov brothers were among those elected to its central council. The Intermovement unsuccessfully promoted the New Union Treaty and gained little popular support. Their most enduring success debuted at a rally on October 18, 1991, not long before the referendum on Ukraine’s declaration of independence: a red, blue, and black tricolor flag that would eventually become the flag of the Donetsk People’s Republic.

Again citing Novosti Donbas, DEPO reports that former KGB General Oleg Kalugin had accused all of the Intermovements of being created by the KGB. According to Kalugin the Intermovements were meant to undermine nationalist separatism in the republics of the Soviet Union.

One might question whether or not Kalugin is the most reliable source on this subject. He had been demoted for criticizing KGB chief Yuri Andropov during Andropov’s anti-corruption campaign, and also allegedly protected CIA spies in the USSR.

Kalugin was elected to the Congress of People’s Deputies on the Democratic Platform of the CPSU in 1990 and supported the anti-communist reformer Boris Yeltsin. After securing the break-up of the KGB, Kalugin moved to the United States in 1995. From the 1980s onward Kalugin had been an opponent of the socialist system and a supporter of those who would destroy it.

Whatever the truth is behind Kalugin’s statements, it is evident that an enthusiastic clique of academics, even with KGB backing, could not create a separatist movement out of thin air. The proof is in the results of the December 1, 1991, referendum, in which 92% of voters said “YES” to the Declaration of Independence from the USSR.

The Intermovement for Donbas failed to raise support for a renewed USSR, but the separatist movement would grow larger and stronger with every crisis that shook independent Ukraine.

The Shock Year

The act of independence immediately triggered a years-long economic crisis which was the driving force behind Ukraine’s growing separatist and anti-government movements.

The March 1990 elections to the Congress of People’s Deputies and Supreme Soviet of Ukraine had been the first to allow non-communist candidates to participate. Liberals, nationalists, and other anti-communist groups like Rukh entered the legislature. During the reaction to the August Coup in 1991 the Communist Party of Ukraine was banned and the nationalist groups remained as the most organized factions in the legislature.

As Ukrainian news site STRANA opined in its retrospective on 30 years of independence:

“The nerve of 1992 is the first attempt by the country’s leadership to deviate from the framework set by 1991. When Ukraine arose as a result of a compromise between very different groups (including representatives of the party apparatus, directors of enterprises), most of [them], as well as the population as a whole (which was shown by voting for Kravchuk, and not for Chornovil [leader of Rukh]), were not nationalistic and did not want to completely break with Russia.”

The newly independent government rapidly implemented policies which served nationalist and anti-communist ideologies irrespective of the material impact they had on the people of Ukraine. Per STRANA, “the nationalist tilt and the growing tension in relations with Russia became a serious factor in internal destabilization.”

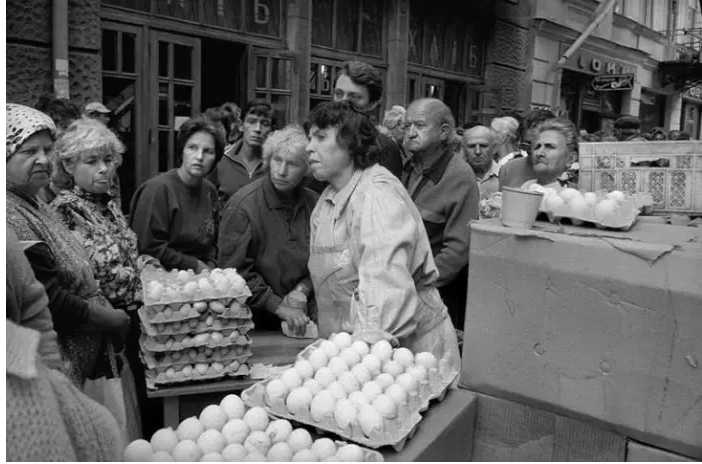

The year 1992 was immediately characterized by economic “shock therapy.” On January 2, 1992, all price controls were released and the market was allowed to dictate prices on all consumer goods. The stated goal of this policy was to find balance between the shortage of goods and the large amount of money that the public held with nothing to buy. The “solution” to the “problem” of the public having too much money was predictable: The shelves were full of goods once more but prices increased by 2100% by the end of the year.

Inflation was accelerated by the spike in oil and gas prices as Ukraine lost the preferential rates it had enjoyed in the Soviet Union. Despite warnings from Moscow and the National Bank of Ukraine that the country would have to pay world prices if it exited the “Ruble Zone,” the government decided to drop the ruble as Ukraine’s currency by year-end.

New national borders interrupted the industrial sector, costs soared, demand fell (especially in state-driven industries like defense and science), and production crashed. For the first time in living memory, Ukrainians experienced the terrors of unemployment, price gouging, and starvation in a time of plenty.

In a Year, We All Became Impoverished Millionaires

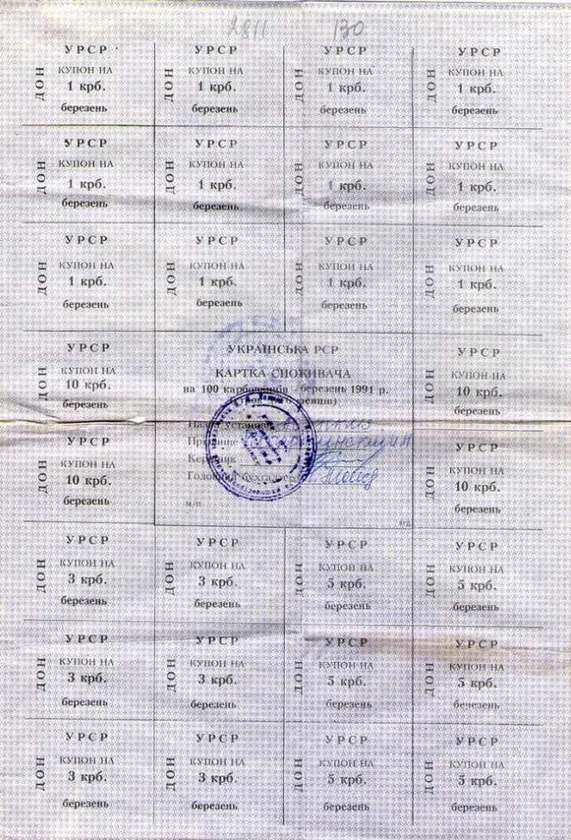

The monetary crisis was an indirect result of the USSR’s final Five-Year Plan, developed under the principle of “acceleration.” Starting in 1990 the Union Republics were forced to issue “Consumer Cards” alongside wages to help ration basic goods like bread and sugar.

The cards were perforated sheets of tear-off tokens that were printed in color and valid only if stamped by the employer or issuing agency. These were commonly referred to as “coupons” in Ukraine (as in English this comes from the French word couper, “to cut”). The main obstacle to counterfeiting was the limited availability of color photocopiers, which became increasingly accessible after the borders were opened to Western trade.